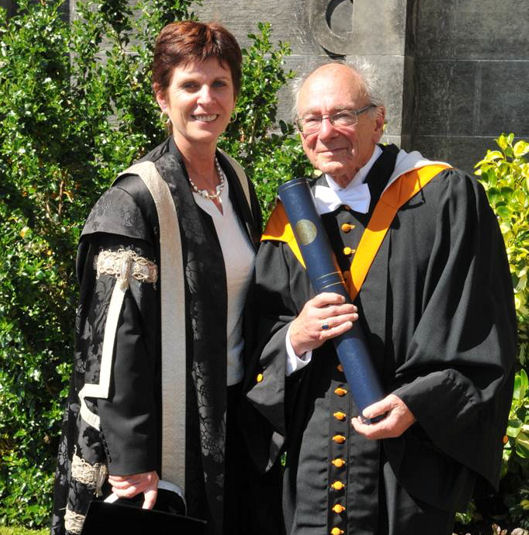

Laureation Address – Professor Stanley Hoffmann

Professor Stanley Hoffmann

Honorary Degree of Doctor of Letters

Laureation by Professor Nick Rengger

School of International Relations

Tuesday 19 June 2012

Vice-Chancellor, it is my privilege to present for the Degree of Doctor of Letters, honoris causa, Professor Stanley Hoffmann.

Stanley Hoffmann is a unique figure in the contemporary academy. He has world wide eminence in three fields – International Relations, French Studies and European Studies – has published 19 books, countless articles and book chapters in all of them, and taught literally of thousands of students at all levels at Harvard, which became his intellectual home. This would surely be thought enough for anyone, but on top of that he has been a leading public intellectual on both sides of the Atlantic, debating many central issues of our time over nearly fifty years. In all these contexts, his remarkable talent for pulling together things that others usually try to keep separate is readily apparent. As Michael Sandel, one of his Harvard Colleagues has remarked, ‘You live it and breathe it when you listen to [Stanley Hoffmann] because it’s really textured by deep knowledge of history, philosophy, sociology – he weaves all the strands together’.

Stanley Hoffmann was born in Vienna in 1928, moving with his mother to Nice in the early 1930s and then on to Paris in 1936. Although baptized as a Protestant, his mother’s family fitted the Nazi racial classification of Jews and so after the German invasion, the young Hoffmann and his mother fled Paris and returned, eventually, to Nice, initially in Vichy, then part of the general occupation. He has spoken movingly about how his experiences of this time have shaped his general outlook; an understanding of the often brutal realities of power – and the fickleness of fate – but also the conviction that there is (in a phrase of Albert Camus, an author he greatly admires), ‘more in man to be admired than to be condemned’.

In 1947, he enrolled as a doctoral candidate in law at the Institut Sciences Politiques, in Paris and then, in 1951 arrived at Harvard to read for the AM in Government which he received in 1952. Appointed as an Instructor in 1955, he has remained at Harvard ever since, becoming a professor in the Government department and eventually, in 1997, the Paul and Catherine Buttenweiser University Professor, one of the most distinguished chairs that the distinguished university can award. Along the way, and in addition to all those students he has taught – one of his colleagues has said that ‘he probably holds the record for the greatest number of courses taught in Harvard’s core curriculum’ – he contributed to the institution in many important ways; helping to create the hugely influential social studies concentration in the 1960s and helping to found and, for the first 15 years of its life, direct what is now the Minda de Gunzberg Centre for European Studies, where he remains a fellow and where his recorded voice greets callers who telephone the centre. He has said that on arrival at Harvard he felt instantly at home, and often describes himself, with a smile, as French, and a citizen of Harvard.

His scholarly contributions in all his chosen fields have been immense. In International Relations, he was an important voice in the theoretical debates that have helped to shape the modern study of international relations in the 1960s and 70s, helped to pioneer the reintegration of ethics and international relations in his classic 1981 study Duties Beyond Borders, wrote path-breaking essays on intellectual history and international relations and has been a leading commentator on American foreign policy for over forty years. But for all this he is perhaps even more as a teacher than a writer. His course on ‘Political Doctrines and Society: Modern France’, which he taught for over thirty years, became legendary at Harvard, as did his celebrated course on ‘War’ which had an enormous reading list; so large in fact that students might find they were expected to read Tolstoy’s War and Peace for simply one of the three lectures the course had in a given week. Some students apparently found this rather a lot and queried it with their professor, who imperturbably replied that of course, while specific assignments would be given out for each week, the rest of the reading list should be seen as ‘merely essential’.

Amidst the plurality of his interests, one conviction has consistently stood out: a fierce commitment to the values of a liberal society. But this liberalism is very different from the liberalism that has dominated academic political philosophy – and to some extent at least practical politics in liberal societies. It is the liberalism he shares with his mentor Raymond Aron, and with his great and good friend Judith Shklar, who coined a phrase for it: she called it the liberalism of fear; the recognition that the root of liberal politics is the fear of arbitrary power, whether exercised by states, social movements, ideologies, corporations, fashion or anything else. Such liberalism is a hard calling and a continuous one, not something that can ever be considered finished or accomplished. His course on ‘Ethics and International Relations’ often concludes with the last two paragraphs of Camus’ La Peste, where after the plague, Camus tells us, the rats will return to the city. The victories we win, in other words, are always provisional; which does not mean of course, that they are not victories. By combining a realism that is rooted in the lived reality of the twentieth – and now twenty-first – century with a humanistic vision rooted in an astonishing breadth of learning, Stanley Hoffmann shows us how understanding our times means engaging with them, with neither illusion nor despair, but with a clear eye and firm tread.

Vice-Chancellor, in recognition of his major contribution to Humanistic learning in many fields, I invite you to confer on Stanley Hoffmann the Degree of Doctor of Letters, honoris causa.

Category Awards