Wilful blindness

They made us sing…’ by Owen Maseko © (image and painting)

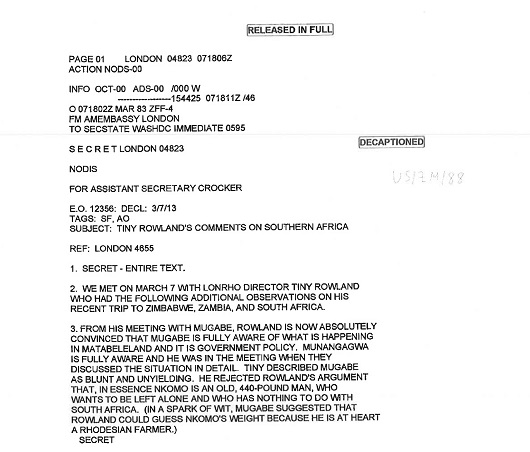

Britain was “wilfully blind” to atrocities committed by Robert Mugabe’s army in Zimbabwe in the early 1980s, according to St Andrews researcher Dr Hazel Cameron.

In a paper published this month (April 2017) by The International History Review, Dr Cameron has revealed how Britain stood by and engaged in a “conspiracy of silence” while thousands of innocent civilians were massacred in Matabeleland.

Dr Cameron’s study provides a critical new lens into the 1983 massacres – known as ‘Gukurahundi’ – by revealing for the first time how British officials were “intimately aware” of atrocities as they unfolded.

Using previously unseen material – obtained under the Freedom of Information Act – Dr Cameron’s findings implicate Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government and Robin Byatt, the British High Commissioner in Harare, for their “wilful blindness” during the period of violence.

Dr Cameron’s research – which was self-funded – investigated the episode of post-colonial state violence in the newly independent Zimbabwe committed by an army unit known as the ‘Fifth Brigade’. The unit was a division of the Zimbabwean National Army and some of its soldiers were trained by the British Ministry of Defence.

BMATT (British Military Advisory Training Team) training members of the new Zimbabwean army. Copyright © Zimbabwean National Archives

The episode followed Zimbabwe’s first Prime Minister Robert Mugabe’s launch of a “massive security clampdown”, which started with a strict curfew, arbitrary arrests and detentions without charge, in Matabeleland North in January 1983.

For the following nine months, the Fifth Brigade killed, mass tortured, raped and burned alive thousands of the Ndeble people claimed to be dissidents or affiliates of the opposition party ZAPU (Zimbabwean African People’s Union).

In the first six weeks alone, between three and five thousand unarmed civilians of North Matabeleland were killed by the Fifth Brigade, who told their victims they had been ordered to “kill anything that was human”. The total number of murders during the Gukurahundi period is estimated to be “no fewer than 10,000 and no more than 20,000”.

Copyright © Zimbabwean National Archives

Dr Cameron, a lecturer in International Relations at St Andrews, said: “There can be no doubt that Gukurahundi was Zimbabwean government policy. It is quite clear from these documents that one of the major concerns for the British at the time was the reputation of their own army and British public opinion, as opposed to the ongoing atrocities and human violations in Matabeleland.

“Instead, the Zimbabweans who were of concern to the British government, and influenced their diplomatic approach, were the many white Zimbabweans living in the affected regions, and who were unaffected by the extreme violence of Fifth Brigade.

“That the British government chose to adopt a policy of wilful blindness towards the atrocities undoubtedly constituted naked realpolitik. Mugabe himself was said to view the British response favourably, saying ‘you have to hand it to the British, they know how to behave in this kind of situation’.”

For the study, Dr Cameron scoured 2600 pages of documents, focusing on sources dating from January to April 1983 to establish what knowledge was available to the British and US governments about the “persistent and relentless” atrocities taking place at this time, as well as the diplomatic approaches pursued by both governments in response to events.

Commenting on her success in obtaining a “treasure trove” of both US- and UK-government correspondence through Freedom of Information requests, she said: “I was astounded when a large, unmarked box of so much uncensored material arrived at my office.”

The documents were obtained from the British Cabinet Office, British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, British Ministry of Defence and United States Department of State. Dr Cameron describes the information, which is not in the public domain, as “a real treasure trove”.

The unique dataset provides minutes of meetings and other relevant communications between the British High Commission (Harare), the Prime Minister’s Office, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Cabinet Office and the Ministry of Defence in London, as well as the US Department of State and the US Embassy in Harare.

Importantly, Dr Cameron analysed declassified documents from the US – which “demonstrated concern” and a more victim-centred approach during the same period – to highlight the UK Government’s approach was to turn a “blind eye” to the victims of gross abuse.

In a cable seen by Dr Cameron from Robin Byatt to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Geoffrey Howe, Byatt refers to Britain’s “important” interests in investment and trade (worth £800m and £120m in 1982), despite the “occasional Zimbabwean perversity”.

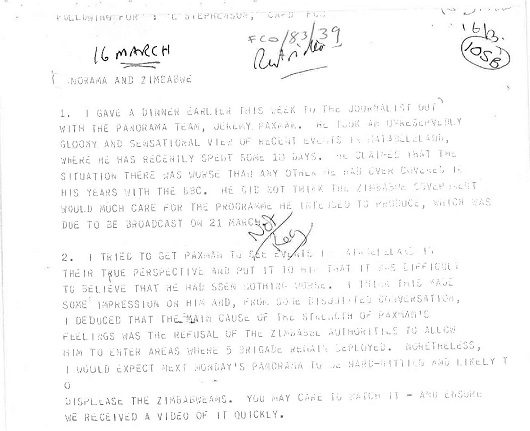

Byatt was unsettled by the arrival of Jeremy Paxman in March 1983 with a small Panorama documentary crew, with the British High Commission claiming that Paxman was taking an “unreservedly gloomy and sensational view of recent events”.

Jeremy Paxman’s BBC Panorama documentary on Gukurahundi

Dr Cameron continued: “The rationale for Britain’s inertia in Zimbabwe when faced with grave violations of human rights is expressed clearly in numerous communications between Harare and London. This includes Britain’s determination to maintain good diplomatic relations with Mugabe in order to protect their significant British economic and strategic interests in southern Africa.

“The dataset also identifies that it was of great importance to Mugabe that the economically viable whites stay in Zimbabwe, whilst it was equally important to the Thatcher government to take measures to prevent the possibility of ‘a major exodus’ of Zimbabweans to the UK.”

“Bystanders – other Governments, NGOs and the UN, for example – should take a more proactive role in these situations; diplomatic intervention could reduce casualties,” said Dr Cameron. “Britain was in a very strong position to take a stance against Gukurahundi, but it was too fearful.”

Gukurahundi only came to an end seven years later with the signing of the Zimbabwean Unity Accord of 1987, which made no recognition whatsoever of the victims of the violence. There was no public admission of guilt for the atrocities or measures proffered for reparations. Instead, a blanket amnesty was offered to all those involved in the Matabeleland Massacres.

Dr Cameron’s research is ongoing, with the current findings representing an analysis of only a small number of the documents from a brief window of time. She is currently writing a book based on her research, which will be published by Hurst & Co in 2018.

Dr Hazel Cameron – who is interested in the crimes of the powerful and the role of external institutional bystanders – believes strongly in “giving a voice to the oppressed”.

Dr Cameron first learned of Gukurahundi when backpacking through Matabeleland in 1999. She was struck by the many surviving adults “still living in fear” and found herself driven to “illuminate a hidden part of Africa’s history”, thus giving a voice to the powerless and victimised.

Exactly ten years later she received her PhD from the University of Liverpool for a thesis on ‘External Institutional Bystanders to Genocide: Case Study Rwanda’. Today, she is part of a community of scholars – the International State Crime Initiative – working to advance current understandings of state crime.

She concluded: “It is quite clear from the material I have uncovered that, apart from the immediate perpetrators, external bystanders have to be held accountable to some extent for the unbridled human rights abuses that took place in Zimbabwe in early 1983.

“One child survivor of Gukurahundi succinctly summarises the unethical role played by Britain in Zimbabwe through its consistent lack of intervention: ‘there was this conspiracy of silence that took place in the 1980s’.”

Speaking today, survivor Thembani Dube described Dr Cameron’s work as “sterling”.

Gukurahundi survivor and Human Rights Activist Thembani Dube has commended Dr Cameron’s research. He said: “Dr Cameron unravels the complicit role of the British government of Margaret Thatcher very well in this commendable paper. The hard evidence presented of the official British and US government communications regarding this atrocity are revealing.

“The Matebele lives, including those of children and pregnant women, were sacrificed at the altar of British economic interests in Zimbabwe, domestic political interests in the UK, and cold war politics.

“The most important issue at hand today for the people of Matebeleland regarding the important revelations in this paper is their call for ‘Truth, Justice and Reparations’ for their suffering.

Victims were buried in mass burials and no death certificates were issued to families devastated by Gukurahundi.

Dr Cameron says that survivors today are “still living in fear” even as adults, although many – like Thembani – are now activists looking for justice.

Photo: Anonymous

“Dr Cameron’s sterling work is welcomed by the people of Matebeleland and contributes significantly to the full understanding of the key players in the Gukurahundi atrocities. It also adds to the strong calls for an international investigation.”

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Unity Accord on 22 December 1987, an accord between the country’s two political parties: the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), which brought an end to Gukurahundi. A blanket amnesty was offered to all who were involved, including all members of the security forces who had committed human rights violations.

National Unity Day is now a public holiday in Zimbabwe, celebrated on 22 December. However, the government has prevented any public ceremonies or memorials remembering the victims of Gukurahundi.

In one village in Matabeleland 19 women and 1 man was burned alive in a hut – locals have memorialised the victims with their own tribute. Photo: Anonymous

Top and homepage tile images are (top image) ‘They made us sing…’ and (homepage tile image) ‘Tears of the old ladies’ are by Owen Maseko, one of Zimbabwe’s most prominent artists, who uses art as a form of resistance against the state crimes of the Government of Zimbabwe. In March 2010, he was arrested less than 24 hours after his new exhibition opened in Bulawayo, solely because his art was a portrayal of Gukurahundi.

Copyright (painting and image) © Owen Maseko

Category Public interest stories