A 20th-century bromance

The friendship of JM Barrie and Captain Scott

“I never met a man in my life whom I admired and loved more than you, but I never could show you how much your friendship meant to me, for you had much to give and I nothing”, wrote Captain Robert Falcon Scott, as he lay dying in the Antarctic, in a final letter to University of St Andrews rector JM Barrie.

Captain Robert Falcon Scott.

Photograph: PA

“I well remember how, having found the entrancing man, I was unable to leave him.” – JM Barrie

The pair had first met at a society party in London six years earlier. Scott gave Barrie the book he had written about his expedition, and Barrie invited him to a rehearsal of Peter Pan in return. The two became inseparable, and in the autumn of 1909 Barrie became godfather to Scott’s son Peter, believed to be named after “the boy who never grew up”.

It was an unlikely friendship: Barrie was weak and skinny as a result of his poverty-stricken childhood while Scott was a heroic adventurer. However, Barrie was fascinated with explorers all his life – his favourite book as a child was RM Ballantyne’s The Coral Island. Meanwhile, Captain Scott had wanted to be a writer in his youth, until family pressures forced him into a career in the navy.

This relationship had a significant impact on the explorer, and can be seen to have helped to shape the way Scott understood and narrated his own Antarctic experiences (Moriarty, 2018).

“JM [Barrie] has a fatal touch for those he loves. They die.” – DH Lawrence

Scott’s final letter to JM Barrie sought to heal a rift. The friends had become estranged just before Scott left for his final polar expedition:

“It hurt me grievously when you partially withdrew your friendship or seemed so to do. My attitude towards you and everyone connected with you was always one of respect and admiration.”

Terra Nova Expedition

Photograph: Bettman/CORBIS

Captain Scott died on 29 March 1912 in a tent alongside Edward Wilson and Henry Bowers. Lawrence Oates limped out to die in the snow, one leg destroyed by frostbite, remarking, “I am just going outside and may be some time.” The undelivered letter was found among Captain Scott’s possessions the following November, when the bodies were discovered.

“My dear Barrie, we are pegging out in a very comfortless spot.”

The grave of Edward Adrian Wilson, Henry Robertson Bowers and Robert Falcon Scott.

Photograph: PA

Barrie was left bereft and wrote his own letter in response, published in The Times in February 1913, in which he explained Scott’s achievements as a legacy for Britain as a whole:

“Almost every Briton alive has been prouder these last days because a message from a tent has shown him how the breed lives on.”

Barrie’s Rectoral Address, University of St Andrews 3 May 1922

During his rectorial address, Barrie pulled the letter from his pocket:

“I have the little filmy sheets here.”

And he quoted:

“Goodbye–I am not at all afraid of the end, but sad to miss many a simple pleasure which I had planned for the future in our long marches. … We are in a desperate state–feet frozen, no fuel, and a long way from food, but it would do your heart good to be in our tent, to hear our songs and our cheery conversation…”

Barrie went on to reflect:

“What is beauty? It is these hard-bitten men singing courage to you from their tent.”

When Barrie himself died years later, Scott’s letter was still in the breast pocket of one of his jackets. He had carried it with him for over 20 years.

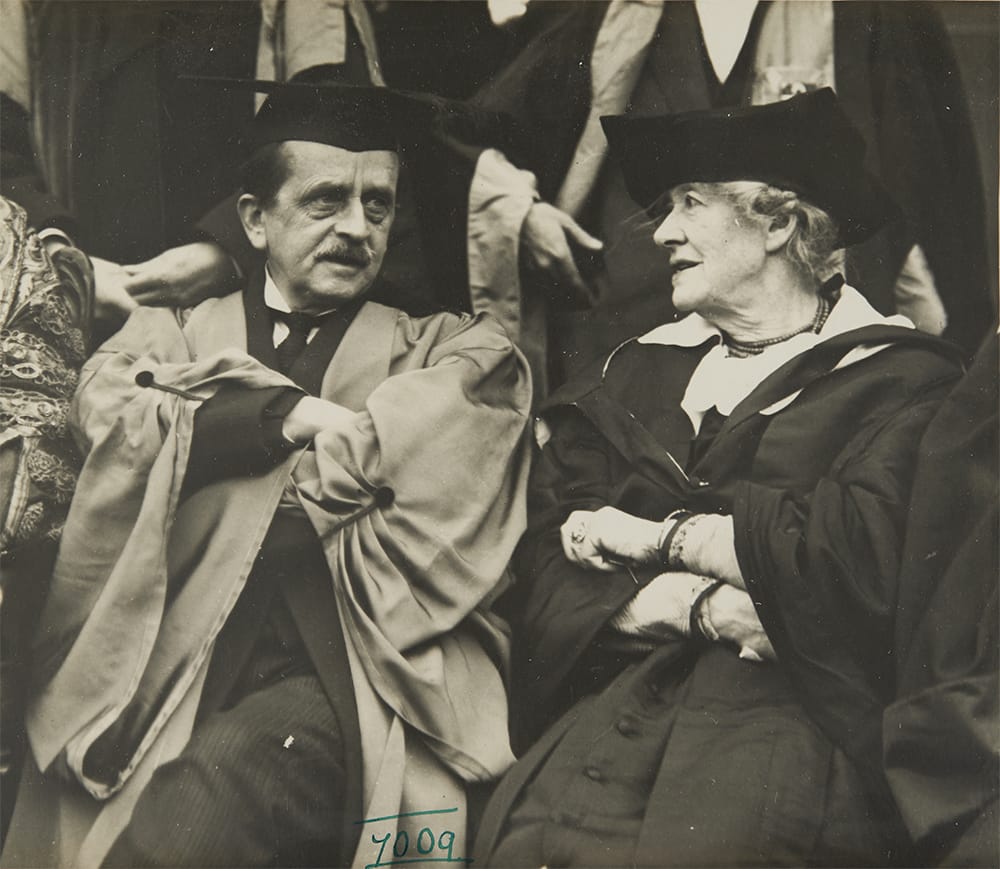

JM Barrie at his rectorial induction, 1922.

Photograph: University of St Andrews