Crumbling coast: saving Scotland’s heritage

Archaeologists at St Andrews have brought local communities together to find solutions for saving some of Scotland’s most endangered historical sites from coastal erosion.

One archaeological research team at the University of St Andrews has developed an extensive survey of Scotland’s coastline, recording not only threats to historical sites, but also the effects of climate change. Through their work, they have empowered local communities to take action to record and preserve historical sites which are threatened by coastal erosion and weather.

The sea poses one of the greatest natural threats to cultural heritage sites located on the coast. It is estimated that £400 million worth of property and infrastructure around Scotland’s coastline is at risk due to the effects of erosion.

Monitoring and taking action to protect Scotland’s coastal heritage sites is an extremely difficult task. For one thing, the length of the coastline (18,670km) makes it difficult to find the resource to monitor coastal changes, especially in difficult-to-reach locations. In addition, there are well over 12,000 sites to oversee – no small task for Scotland’s archaeologists.

Archaeologists at St Andrews decided to tackle this problem from two angles. First, they updated the national records of coastal sites and digitised them. Second, they brought groups of community volunteers together to survey and protect cherished heritage sites.

Eye on the shoreline

In order to understand the full extent of Scotland’s coastal heritage sites and to inform decisions about resource allocation, Historic Environment Scotland (formerly known as Historic Scotland) commissioned a series of coastal zone assessment surveys starting in 1996. These surveys recorded all archaeological sites as well as the geology, geomorphology and erosion class of the coast.

In 2000, Historic Environment Scotland asked Tom Dawson from the School of History to take over the management of the coastal surveys. Together with Historic Environment Scotland, Dawson established the SCAPE Trust (Scottish Coastal Archaeology and the Problem of Erosion), a charity set up to research and promote the archaeology of Scotland’s coast. Through SCAPE, Dawson developed ways of improving the coastal survey process: what was once stacks of handwritten paper reports became digital documents, and surveyors started using GPS (global positioning system) to record locations, and GIS (geographic information system) to visualise and analyse data.

At the same time SCAPE started managing a community project called Shorewatch. The Shorewatch project encourages and assists local communities to locate, record and monitor archaeological sites around Scotland’s coast. These local community members were invaluable to the coastal survey as they were able to record sites that had previously been unreported and were able to quickly report damage or changes that occurred after storms or high tides.

The coastal surveys drew attention to the fact that there were more sites in need of protection than there were resources available to do so. Even with a strong volunteer base, surveyors were unable to keep up with a rapidly changing coastline. Surveys became quickly out-of-date as the next storm or tide shifted sediments or caused further damage to a site.

The Wemyss caves ShoreDIG

The Wemyss Caves are a collection of caves located in East Wemyss, near Kirkcaldy, Fife, which house one of the highest concentrations of Pictish cave carvings in Scotland. The carvings feature abstract symbols and animal representations typical of the Pictish art style and are around 1,500 years old.

Archaeologists from SCAPE and archaeological surveyors from The York Archaeological Trust (YAT) ensured a ‘digital future’ for the Wemyss Caves.

This project resulted in a highly detailed 4D digital reconstruction of the caves, created using laser scanning, structure mofrom motion photography, Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) and aerial photography.

The digital reconstruction was created in collaboration with the Save the Wemyss Ancient Caves Society (SWACS), with the support of Historic Environment Scotland and Fife Council.

“To put the rarity of the Wemyss Caves in context, they contain 49 of only 60 examples of Pictish symbols documented in caves and account for five of the eight known caves in Scotland that have recorded Pictish symbols in them.”

– Picts and the Wemyss Caves, March 2018

Wemyss Caves carvings

Over the years, the caves have been subject to neglect and damage. Antiquarians first recorded the carvings in the 1860s, and of the 49 symbols documented then, only 26 are still visible today. The others have been destroyed as a result of cave collapse and vandalism. At present, structural decay, coastal erosion and vandalism present a great risk to the history held within these caves. The caves are now marked as a priority site on the SCHARP Sites at Risk map.

The team also worked closely with members of the Wemyss community to record memories, gather old photographs of the caves and bring the history of the caves to life. The films that were made were an important part of the project, and each cave had an accompanying film. For example, the video ‘Standing on the Shoulders of Giants’ features members of SWACS as antiquarians, thus shining more light on the importance of the caves.

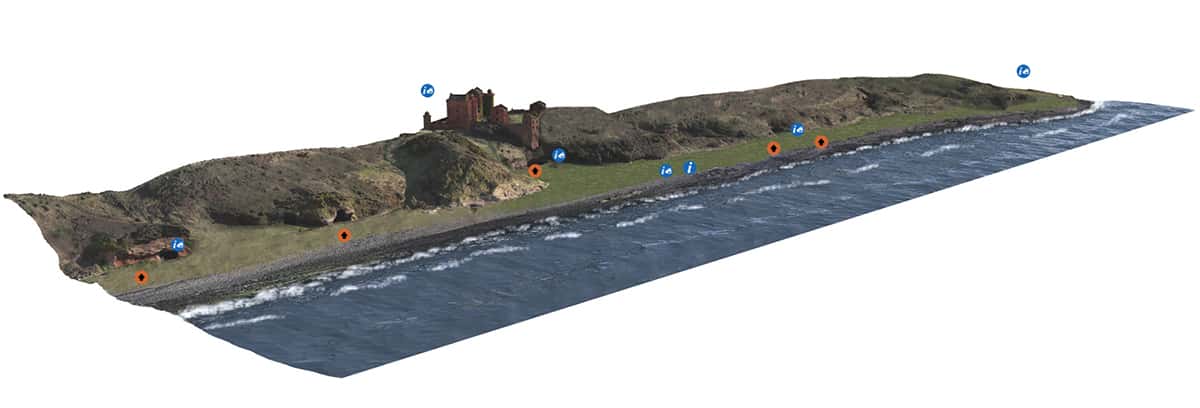

To create the digital reconstruction, a number of techniques were used. YAT laser scanned and photographed the entire length of coastline from the Court Cave at East Wemyss to the Gasworks Cave halfway to Buckhaven. At the same time they digitally recorded the interior of every cave.

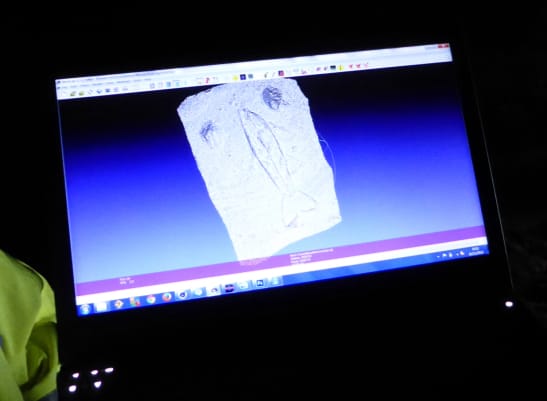

The team also utilised structured light scanning, where precise mathematical patterns of light were projected onto the cave wall, and the distortion of the pattern as it met any unevenness was recorded and measured to create an accurate model of the wall. Watch an example of this light scanning technique at Jonathan’s cave, one of the Wemyss caves which has the highest concentration of carvings.

In addition to this technique, volunteers from SWACS and the local community carried out RTI to capture the cave’s intricacies. RTI is a photographic technique which stitches a series of photographs together into one image. The RTI images can be viewed in the 4D reconstruction, and they allow users to examine the carvings using a virtual torch to illuminate subtle details difficult to see in low light conditions.

During the course of the project, the team made some surprising finds. For example, the scanned images revealed original details of the carvings which were no longer visible to the naked eye. In one instance, new fins were visible on a carving of a leaping salmon which, due to the passing of time had nearly disappeared completely.

Alongside the digitisation of the caves, the community involvement in this project was integral in documenting the centuries of history the caves present. At the caves and at the East Wemyss Senior Citizens Centre, Tom Dawson and his volunteers recorded video memories of residents and copied old photographs of the Caves and East Wemyss, generously shared by scores of local residents.

The information gathered through the Wemyss 4D project provided a vital understanding of the geographical context of the historic carvings and highlights the potential long-term coastal risks to the caves caused by coastal erosion and structural failure.

You can find out more about the Wemyss caves project via the SCHARP blog and view the interactive 4D map of the caves on Wemyss Caves 4D.

Saving the coast

It was clear from the experience with the Shorewatch project that more needed to be done to help save at-risk coastal heritage sites. Surveys alone were not going to solve the problem. However, with over 12,000 identified sites and limited resources, the main question for the SCAPE team became: how do we make the most with what we have?

The SCAPE team decided that they needed to prioritise the sites. Between 2005 and 2010, they undertook a series of reports on the coastal surveys and prioritised sites based on two key factors:

- actual or potential value of each heritage site

- the level of threat each heritage site faced

Sites which were deemed to have high value and which had a high threat level were prioritised first. After additional consultation with local and national heritage managers, a final database of the prioritised sites was created, which also included suggested actions to be undertaken at each site.

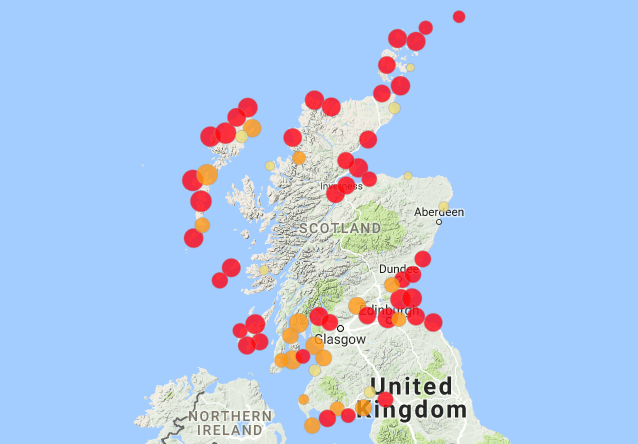

However, these reports revealed that almost 1,000 high priority sites needed to be reassessed as their condition had significantly worsened since the original surveys took place almost 15 years previously. Based on previous success with community-aided archaeology, a new project was born: SCHARP (Scotland’s Coastal Heritage at Risk Project).

SCHARP was funded by a grant from Historic Environment Scotland and the Heritage Lottery Fund. The project was also supported by the Crown Estate and the University of St Andrews. In 2014, it won the Best Community Engagement Archaeology Project at the British Archaeological Awards.

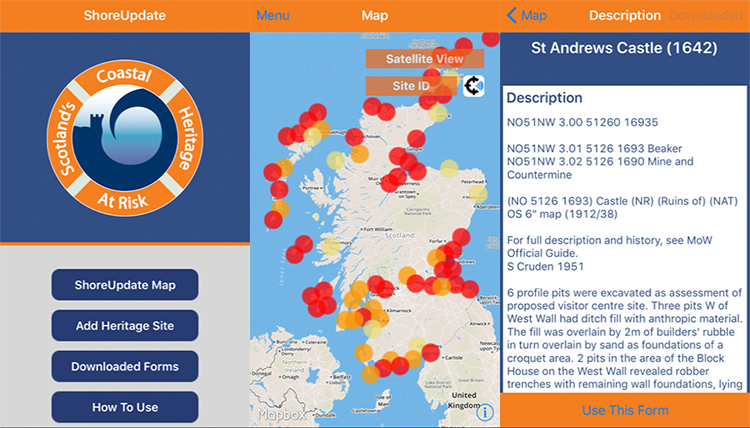

ShoreUPDATE

At the heart of SCHARP, ShoreUPDATE was an initiative started in 2012 to work with volunteers to revisit and update sites on the prioritised list. As part of the update, the team created an app which allowed a two-way exchange with the public: the app provided heritage data from the coastal surveys (including maps to the sites), and the public were able to upload photographs and information through a multiple-choice recording form (in areas where the was no mobile signal the information would be cached for uploading later). This app was voted Best Archaeological Innovation in 2014 at the British Archaeological Awards.

In the first three years of the project, 1,100 volunteers submitted photographs, site surveys, and new site records to the ShoreUPDATE app. Based on their input, the SCAPE team were able to shortlist 145 of the most at-risk and significant coastal sites in Scotland.

The updated list is helping Historic Environment Scotland in their allocation of resources to threatened sites.

ShoreDIG

A further element of the SCHARP project was ShoreDIG, which asked the public to nominate prioritised sites for projects and to outline possible actions to be undertaken.

From 2012 to 2016, a total of 14 ShoreDIG projects were carried out, in which community members receive on-site training and work in collaboration with heritage professionals to bring their project ideas to fruition.

Examples of ShoreDIG projects:

- Loch Paible: excavated Iron Age stone structures, ditches and pits in North Uist that were rapidly falling into the sea.

Volunteers excavate stone structure, ditches, and pits at the mouth of Loch Paible. - Eyemouth Fort: conducted surveys and historical research to create a 3D digital model of a 16th-century fort.

Image by UK Civil Air Patrol - Meur Burnt Mound: excavated and relocated a Bronze Age burnt mound on Sanday, in Orkney, to save it from being destroyed by storms and erosion.

Volunteers work on relocating the burnt mound at Meur on Orkney. - Newshot Ship Graveyard: surveyed and documented a remarkable group of vessels in a boat graveyard near Newshot Island. As a result of the project, the site is now protected as a Scheduled Monument in recognition of its national importance as a rare survival of an assemblage of vessels involved in the making of the Clyde. The project won Best Community Project in the 2018 British Archaeology Awards.

Volunteers

The success of SCHARP is thanks to the 1,233 volunteers who gave up their time to get involved in ShoreUPDATE and ShoreDIG. Without the help of volunteers, the projects would not have been possible to carry out. Volunteers came from local communities, had an interest in their heritage, and were keen to protect it for future generations. Anyone who wanted to get involved was welcome to join.

“Anyone can learn to do a ShoreUPDATE, they are not difficult things, you don’t need to be a technician to understand how to do them and make useful observations. It’s a good way of getting ordinary people who are not otherwise archaeologically inclined to get out and look at stuff in a new way and appreciate their local history”

– Laurens McGregor

ShoreUPDATE ran 43 training events around Scotland between 2012 and 2016. These catalyst events provided volunteers with all the skills they needed to carry out condition surveys on threatened sites. During the course of the project, 404 volunteers were trained to become surveyors and contributed 695 days to coastal surveys and submitted 1,074 ShoreUPDATE records. A further 486 volunteers contributed over 1,100 days to ShoreDIG activities. Volunteers were given the opportunity to develop a wide range of skills and were pivotal in providing local research, organising events and letting local media know about the site.

While some volunteers had previous archaeological experience, others had no experience whatsoever. A key objective of SCHARP was to attract new audiences to get involved with archaeology for the first time, with an emphasis on those aged 17 to 25. To appeal to a younger audience, the team worked with youth leaders and networks to create fun, time-limited activities which would give volunteers the opportunity to learn new skills. Due to these activities, over 25% of ShoreDIG volunteers were younger than 26.

Volunteers for the project were recruited in a variety of ways. The first step of recruitment would involve the team connecting with local community councils and history societies to get a better understanding of the area. Social media channels such as community Facebook pages worked well for raising awareness and communicating to a broad audience. However, traditional methods such as poster advertisements in village halls and community centres were also successful in attracting volunteers.

The feedback from the volunteers who participated in SCHARP was overwhelmingly positive. With the ongoing impact of climate change, volunteers noted the importance of the project in claiming ownership of their heritage before it is lost forever. Furthermore, people enjoyed being able to interact with others who shared an interest in archaeology and heritage. Personal memories and knowledge about the sites were also shared between the volunteers, with many learning things that they never knew before. For others, volunteering led them to pursue their interest in archaeology, and one volunteer even enrolled in a Master’s course.

Researchers

Tom Dawson

Tom Dawson has been a researcher in the School of History at the University of St Andrews since 2000. Tom has had a varied career which has seen him lead excavations around the world, including sites in Japan, Italy and France. Tom also has a strong connection with Sri Lanka, where for three years he helped to train Sri Lankan colleagues working on an UNESCO World Heritage site in the Sacred City of Anuradhapura. He helped to establish their national monuments record and worked on the recording of a sunken Dutch shipwreck.

Tom began his archaeological experience through volunteering opportunities, which gave him a keen interest in developing community projects to involve local residents. Tom is committed to increasing public participation by creating more opportunities for local volunteers to get involved. His passion for Scotland’s coast has been recognised globally as he continues to educate others on how methods used in Scotland can be adapted to help coastlines at risk around the world.

Between 2010 to 2015, Tom was a commissioner for the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland before it merged with Historic Scotland to form Historic Environment Scotland in 2015. Tom is a member of various archaeological societies, including the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, to which he was appointed Vice President in 2015. Furthermore, he has contributed to numerous publications and was one of the editors of the 2017 book, Public Archaeology and Climate Change.

Joanna Hambly

Joanna Hambly became involved with archaeology at the age of 17 when she volunteered at an excavation in Winchester. With no previous knowledge or experience of archaeology, the opportunity to volunteer provided her with a newfound interest. She developed this interest further by going on to study the subject at the University of Sheffield, which has led to a 30-year career in archaeology. Joanna has had the opportunity to work around the world in places including Sri Lanka, France and Italy. She has also spoken at various conferences and events, sharing her knowledge and expertise on coastal erosion with audiences around the UK and abroad.

Joanna joined the University of St Andrews in 2009 as a research assistant. Prior to this, she spent ten years working as an archaeological curator at the Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire. In this position, she was responsible for running planning services for local authorities and providing educational outreach programmes. Since joining the team at St Andrews, Joanna has worked with Tom on the SCAPE project as the SCHARP project manager.

There are many aspects of archaeology which keeps Joanna motivated, including the variable, physical and outside nature of the work. While there is a still considerable indoor analytical and computer work required, working outside allows her to remain connected with the raw data in a very sociable environment. In Joanna’s opinion, St Andrews is a great place to work, especially when it comes to an understanding of coastal heritage. The nature of the work means that much of the research takes place away from the University, working with external bodies and volunteers, with the full support of the University.

Joanna believes that the achievement of the team at St Andrews, involving so many volunteers in research, is something to be celebrated and is one of the proudest achievements of her career. For anyone who is considering a career in archaeology, Joanna says that it is challenging but equally rewarding. Archaeology is such a multidisciplinary field that an earth sciences, computer science, architectural, art history or medieval history background are all equally valuable to enter the discipline.

Ellie Graham

Ellie Graham is the SCHARP research assistant and has been part of the SCAPE team since 2012. Originally from Aberdeen, Ellie started out in archaeology as a volunteer much like Tom and Joanna. Between 2008 and 2011, Ellie studied Practical Archaeology at the University of Birmingham, where she specialised in urban characterisation. With a background in commercial and community archaeology, Ellie developed her passion for coastal archaeology while working with Arfordir Coastal Heritage in Wales. In her role at St Andrews, Ellie is responsible for promoting SCHARP through the development of talks, workshops and archaeological training events. With a keen interest in community engagement and working with local communities, Ellie provides training and advice to the volunteers on how to accurately record threatened coastal sites.

A global model

The tools and methodology behind the SCAPE projects have inspired heritage groups around the world.

The SCHARP website and app has been used as a model for England’s CITiZAN project, and the Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust in Wales has applied the methodology for working with local groups in their Arfordir Coastal Heritage project.

In the USA, the National Park Service cite SCAPE and SCHARP as an example of best practise. The Florida Public Archaeology Network has been inspired by SCAPE to work with local groups to monitor and report coastal change. Similar groups in Maine and Puerto Rico have set themselves up to involve local communities in archaeology.

Encouraged by the work of the team, the Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland set up their own coastal monitoring programme and employed a member of staff to work specifically on coastal erosion.

“I suggest that our professional organisations can and should develop just a few long-term collaborative strategies for integrating archaeological knowledge of human history. Two examples of tactics show how archaeology and climate change concerns intersect at community and global levels. The first is SCAPE where archaeologists have reached beyond traditional heritage management to empower local communities to document, excavate and conserve coastal archaeological sites…. The key here is archaeological empowerment of local communities as not only first responders but also true knowledge producers.”

– Diane Gifford-Gonzalez, Opening address of the World Archaeology Congress, Kyoto, October 2016

Scotland’s coastal future

The coastal surveys and SCAPE projects have already had a major impact on understanding coastal erosion, climate change, and vulnerable sites in Scotland and abroad, but the SCAPE team are looking ahead to the future.

One area of work they will be delving into in the near future is conducting case studies on the 145 priority coastal heritage sites. These sites will provide understanding of the mechanisms of coastal change and vulnerabilities going forward. They also provide opportunities to have shared conversations about loss of heritage, something which will accelerate as a result of climate change.

“There’s nothing better than an eroding site to bring people together and talk through options.” – Joanna Hambly

By bringing together managers from Historic Environment Scotland, researchers from universities, and the local community, there can be a forward-moving discussion about how to deal with vulnerable sites, whether that be looking into building coastal defences, making 3D models, or developing history projects to remember a site before it is lost.

In addition to looking for new ways to work with threatened sites, the team would like to pick up where they left off with the coastal assessment surveys. Over 60% of Scotland’s coast remains unsurveyed. Areas which are a high priority for new surveys include the coasts of Moray, Aberdeenshire, south Harris, and parts of Orkney and Shetland.

Another aspect of ongoing work for SCAPE is helping to improve Dynamic Coast’s computed model for mapping future coastal change by providing the empirical data gathered from the surveys and SCAPE projects.

“We have a great network of indicator sites that can tell us about coastal change and climate change going forward,” – Joanna Hambly

Climate change will continue to amplify the effects of natural processes on coastal heritage sites. The work undertaken by Tom Dawson, Joanna Hambly and the SCAPE team over the past 20 years has helped Scotland not only identify vulnerable sites, but brought the community together to come up with action plans for monitoring, recording and preserving the coast and sites of great cultural value.

Credits

Graphics and design by the University of St Andrews digital communications team. Content written by John Chapman, Maria Drummond and Jennifer Hamrick, digital communications team.

Aerial images by UK Civil Air Patrol. Jonathan's cave images by RCAHMS (Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Collection). Background images by Jennifer Hamrick. Video and editing by Lewis Wake, digital communications team.

Thanks

Tom Dawson, Joanna Hambly and Elinor Graham for their support and time on this project.

Sources

- Graham Allsop, EL, Dawson, TC and Hambly, J (2017), "Learning from loss: eroding coastal heritage in Scotland" Humanities, vol 6, no. 4, 87. DOI: 10.3390/h6040087

- Dawson, TC (2016), "The steps to prioritizing and undertaking action at sites threatened by climate change: incorporating a citizen science approach into heritage management in Scotland" With a World of Heritage So Rich: Lessons from Across the Globe for US Historic Preservation in its Second 50 Years. US/ICOMOS.

- Hambly, J (2017), "A review of heritage at risk from coastal processes in Scotland". The Scape Trust.

Contact

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +44 (0)1334 46 2108