Smart at first sight

Research at St Andrews explores human bias in perceptions of attractiveness and intelligence.

Are attractive people more intelligent? Not exactly but, according to a series of psychological studies led by Dr Sean Talamas at the University of St Andrews, our perception of intelligence in others is often biased towards those we also perceive as attractive.

Attractiveness halo

From a young age we are taught not to ‘judge a book by its cover’, but first impressions are incredibly important. Before we’ve even opened our mouths, our intelligence is judged by how attractive we appear to others. This is commonly known in the study of psychology as the attractiveness halo effect, whereby attractive people are perceived to possess desirable attributes such as intelligence or kindness.

In fact, attractive people are perceived as more successful, dominant, sociable, trustworthy, mentally stable and intelligent than unattractive people. Attractive people on average make more money than unattractive people, and attractive defendants are less likely to be perceived as guilty.

But what is ‘attractiveness’? Various studies suggest that physical cues indicating a person’s state of health tend to play a large part in perceptions of attractiveness. These cues include facial symmetry, averageness, sexual dimorphism (different characteristics between sexes), skin colour, and adiposity (facial weight). However, people overgeneralise these facial cues to guide their perceptions of personality, strength and aggression in others.

Dr Talamas wanted to find out more about the causes of bias and how accurate first impressions really are. In a series of studies leading up to his thesis, Talamas explored the connection between facial cues, perceptions of intelligence and attractiveness, and actual academic performance. The studies revealed that the attractiveness halo effect causes bias in favour of those who are attractive, which can have serious implications.

Perceived intelligence: Beyond the attractiveness Halo

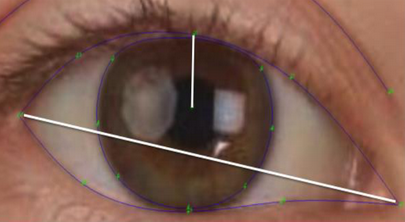

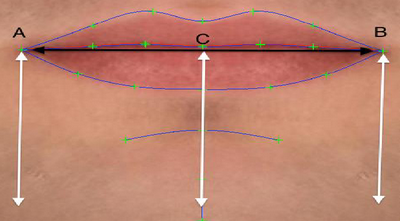

First Talamas wanted to discover whether facial cues to mood (mouth curvature) and alertness (eyelid-openness) affect impressions of intelligence. Mouth curvature refers to the degree of upturn in the mouth (smiling) or downturn (frowning). Talamas and his team conducted four studies in order to investigate the influence of eyelid-openness and mouth curvature.

The studies

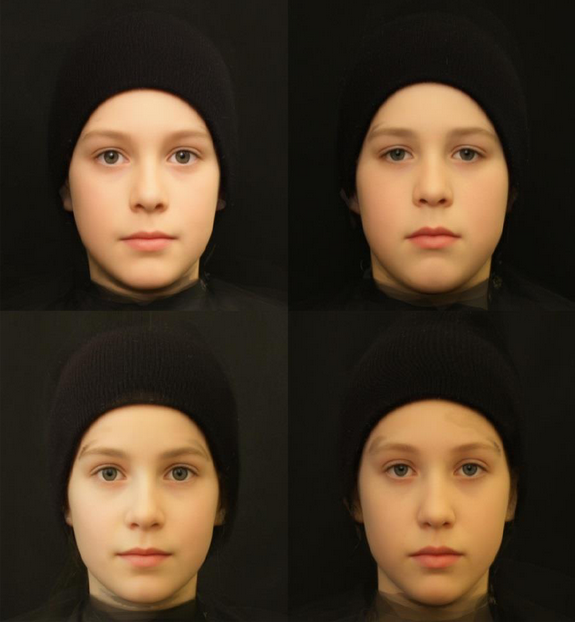

For the first and second studies, 100 images of adults’ faces (50 males and 50 females aged 18 to 33) and 90 images of children’s faces (aged 5 to 17) from a human photo reference agency were used. These faces had no overt facial expressions. Talamas and his team used images of children’s faces because they wanted to investigate the effects of these facial cues on the formation of teacher expectation during early education. Using a seven-point scale, participants were asked to rate the degree of eyelid-openness. Following that, new participants were asked to rate the level of mouth curvature using an unmarked sliding scale with end points labelled ‘downward mouth curvature’ and ‘upward mouth curvature’.

For the third study, the images were digitally manipulated to have altered eyelid-openness and mouth curvature; this was to control any other facial cues that could be impacting impressions. Participants rated the perceived intelligence of the faces using a seven-point scale with ‘not at all intelligent’ and ‘very intelligent’ at each end of the scale.

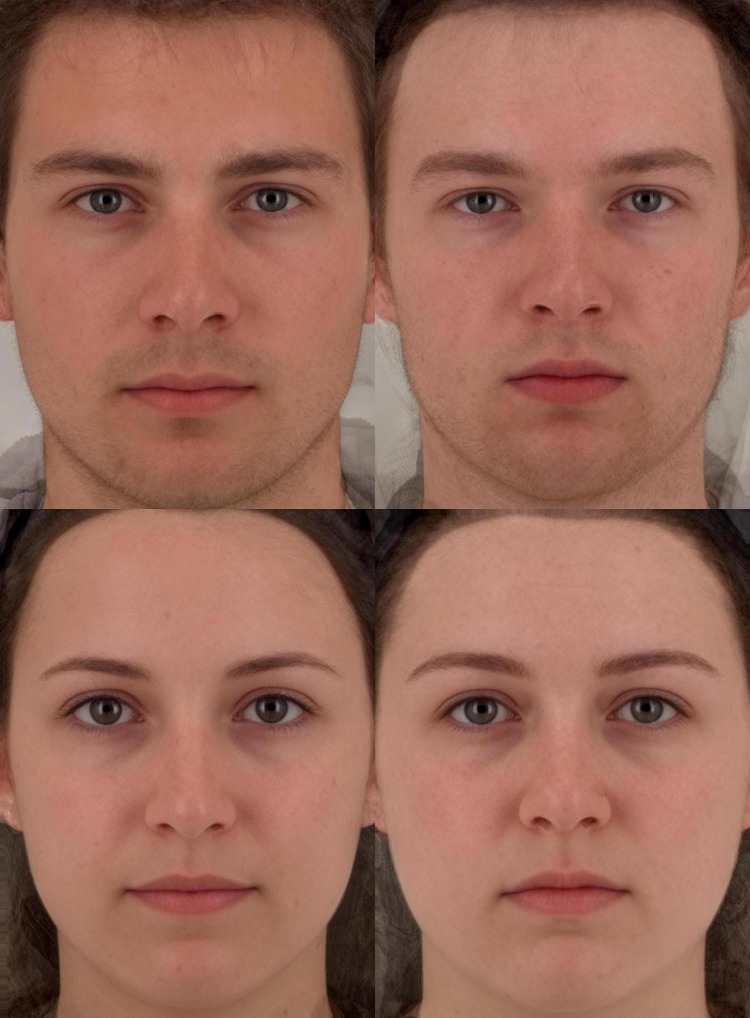

The fourth study examined whether natural variations in these facial cues after sleep restriction could influence perceptions of intelligence. Participants rated the perceived intelligence and attractiveness of two facial images of the same person taken under separate conditions: after normal sleep and after sleep restriction. After being shown two images of the same face, side-by-side, participants were then asked to select the face that had more eyelid-openness and which was smiling more.

Results

The first and second studies found that people with greater eyelid-openness and more upturned mouth curvature are perceived as more intelligent. The third study confirmed that these cues alone can affect perceived intelligence, as demonstrated through digital manipulation. The fourth study found that smiling and eyelid-openness do influence perceptions of intelligence in the same person regardless of their sleep condition. Interestingly, there was no significant relationship between change in eyelid-openness and smiling on perceived attractiveness, yet both had an influence on the change in perceived intelligence.

Implications

Intelligence judgments based on facial cues could affect children most severely because such judgments can lower teacher expectations and hinder educational advancement.

According to the Pygmalion study (Rosenthal and Jacobson), which found that higher expectations lead to an increase in performance, Talamas suggests that educators may be helping more alert-looking students, whom they perceive as more intelligent, to succeed academically by placing higher expectations on them. Therefore, students perceived as sleep-deprived regardless of their actual intelligence may be less likely to receive the same support and expectations from their teachers, and are therefore less likely to perform as well as their more alert-looking peers.

Improvements in sleep patterns and mood for any individual may benefit social evaluations and expectations. Talamas suggests that due to the subtlety of the facial cues, their role in society and their influence on diverse situations, such as teacher expectations and employee recruitment, is underestimated.

Psychology research at St Andrews

The St Andrews School of Psychology and Neuroscience is highly dedicated to a research-based culture of teaching where students are encouraged to experiment and learn in a hands-on environment. The School maintains active links with universities and research institutions both within the UK and abroad, and offers opportunities for a wide range of fieldwork.

But perhaps the most distinguishing feature of research psychology at St Andrews is the high level of support and networking opportunities students receive, as well as the freedom to explore and share individual topics of interest. Sean Talamas describes his personal experience studying and researching at the University:

My lack of a conventional research background before starting my PhD worried me. Yet, as soon as I arrived at St Andrews for my PhD I met my supervisor and my co-supervisor, and was introduced to my soon-to-be fellow lab mates — all of whom I would later count on immeasurably throughout my PhD. It became clear very quickly that I had various people I would be working with side-by-side to help me complete my PhD.

There are not many opportunities in which one has the privilege of working on what they love, whenever they want to work on it, however they want to work on it, and disseminate this work to whomever they want (typically at fully-funded conferences held in exotic locations). There is no doubt that a good research supervisor makes all the difference in the PhD experience, not only in facilitating this independence, but by being a mentor throughout the journey. Thankfully, the University of St Andrews is full of world-renowned research experience, which can provide just that.

Sean Talamas

The root of biases

The other attractiveness halo studies conducted by Talamas and his team focused on questioning whether some people endorse the attractiveness halo more than others. What if perceived intelligence could affect perceived attractiveness; or in other words, what if we thought people were more attractive because we thought they were smart?

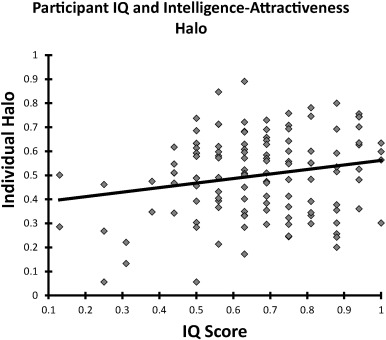

In the second attractiveness halo study, ‘The Influence of Intelligence on the Endorsement of the Intelligence-Attractiveness Halo’, Talamas and his team sought to answer this question by finding out if there was a reason for bias to go in this direction. They hypothesised that the strength of the perceived intelligence-attractiveness correlation depended on the observer’s own intelligence — that smart people were more likely to associate attractiveness with intelligence in others.

The study

Talamas’ team asked 126 participants to rate standardised photographs of 48 children’s faces for perceived intelligence and attractiveness. The 24 male and 24 female children were aged 5 to 16. The photographs were standardised, and the children wore neutral expressions with no makeup or jewellery. The participants, recruited through the University’s pool of psychology students and community members, were aged 18 to 30. Both the participants and children chosen for the study were Caucasian to avoid the possibility of ethnic stereotyping.

The participants first previewed all photographs, presented in random order, for one second and rated the perceived intelligence on a seven-point scale. They then viewed the images again for one second and rated them on a seven-point scale for attractiveness. Finally, the participants were asked to complete the International Cognitive Ability Resource (ICAR) intelligence test administered online.

Results

The results of the study found that participants who scored higher on intelligence tests were more likely to endorse the perceived intelligence-attractiveness relationship. The reasons for this positive correlation could be attributed to a susceptibility to the anchoring effect — the tendency to rely on initial pieces of information (such as someone’s face) to make subsequent judgments — or a bias for self-similarity, where smart people are more altruistic towards others they perceive as smart, because they are self-resembling.

The main conclusion from the study is that, regardless of the reasons, individuals differ in their vulnerability to the attractive-intelligent bias, with those who are more intelligent proving to be more vulnerable.

Implications

As with the previous studies into the attractiveness halo effect, Talamas believes the results of this study have serious implications in education, where children’s academic success is highly affected by the expectations set by their teachers. Teachers’ expectations may be biased depending on perceptions of attractiveness (as discussed in the ‘Blinded by Beauty’ study in the next section), and teachers themselves may be more vulnerable to bias if they have a higher intelligence. Intelligence-attractiveness bias is more likely to occur in education where it also has the potential to do the most harm.

We should strive for a better understanding of the root of biases in an effort to see past them.

Sean Talamas

The Perception Lab

The Perception Lab is where Talamas and his team conducted many of the studies used when exploring the effects of the attractiveness halo. Run by Professor David Perrett, the lab is located in the University of St Andrews and is funded by the ESRC, BBSRC, SINAPSE and the EPSRC. Currently the lab investigates the effect of facial cues on perceptions of attractiveness and health; the size of facial characteristics; and the influence of masculinity, weight and ageing on perception.

The Perception Lab’s website lists current studies and research publications, and also hosts several studies which can be completed online.

Blinded by beauty

In his third study into the attractiveness halo effect, ‘Blinded by Beauty: Attractiveness Bias and Accurate Perceptions of Academic Performance’, Talamas wanted to find out how perceptions of academic performance in the classroom might be biased by perceptions of attractiveness, and how this effect could influence students’ actual future performance.

The study

Talamas and his team asked online participants (recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk) to rate standardised photos of 100 students from the University of St Andrews on their attractiveness, intelligence, conscientiousness and academic performance using a seven-point scale. The participants previewed all of the photos for one second, and then were re-presented with each photo for one second and asked to rate it.

To eliminate the possibility of ethnic stereotyping when judging faces, both the participants and students chosen were Caucasian. The students, aged 18 to 24, wore neutral expressions and were clean shaven and without makeup in the photographs.

The participants’ perceptions of each student’s attractiveness, intelligence, conscientiousness and academic performance were then compared against their actual academic performance.

Results

The results found that attractive people are perceived to be more intelligent and conscientious, and to have a better academic performance. However, the study also found that there is no relationship between attractiveness and actual academic performance. The attractiveness halo effect causes us to be ‘blinded by beauty’ and to assume (often inaccurately) that attractive people perform better academically.

Implications

One of the most concerning implications of the results from the study is that the attractiveness halo effect may have the ability to influence students’ actual academic performance, as previously mentioned using the Pygmalion study (Rosenthal and Jacobson). Teachers may place lower expectations on students they perceive as less attractive.

Dr Sean Talamas

Hard work and dedication are no strangers to Sean Talamas. He completed a Bachelors and Masters in Psychology, along with a Masters in Teaching, all while serving full-time active duty in the United States Air Force. During his service, Sean found a passion for teaching and instructing which led him to pursue a PhD in Psychology at St Andrews.

While I felt my educational background lacked the typical research experience most students have before starting their PhD, it is my background in education and business that got me interested in first impressions of intelligence and how they can have lasting effects on students’ or employees’ performance.

Sean Talamas

Sean’s personal experiences as both a student and teacher made him aware of the obstacles and biases that affect education. “My research investigates the individual differences like the grit and mindset of educators and its influence on perceived intelligence of students,” says Sean. “My interest in this area stems from a belief that we must uncover potential limitations to proper mentorship so that educators can impartially educate regardless of first impressions.”

Besides his research into the halo effect, Sean spends his time sharing his expertise with educators, mentors and coaches in an effort to “help combat the impact of bias teaching practices — for the best antidote to deter unconscious bias is to make it conscious”.

See Sean’s website for his latest blog articles, research papers and project portfolio.

Willypete

Famous among students and staff at St Andrews is Sean’s best friend and proud member of the Perception Lab, Willypete. Willypete has a strong presence in the University, acting as a mascot for the University basketball team, rowing team and Albany Park Wardennial team. He even has his own column in the Psychology MAZE magazine providing life advice to psychology undergraduates.

Famous among students and staff at St Andrews is Sean’s best friend and proud member of the Perception Lab, Willypete. Willypete has a strong presence in the University, acting as a mascot for the University basketball team, rowing team and Albany Park Wardennial team. He even has his own column in the Psychology MAZE magazine providing life advice to psychology undergraduates.

Implications of the attractiveness halo

The attractiveness halo effect causes a misguided assumption of intelligence in those who appear alert, healthy and attractive, whether or not that is actually the case.

The implications of this type of bias are vast. Teachers and professors may believe their more attractive students are more likely to succeed. Job interviewers might unconsciously associate a downturned mouth with being less intelligent.

As Talamas says, the bias towards attractive people can have implications for “any situation in which first impressions can have consequences”.

Ongoing research

As with any research, there is always room for further investigation. Dr Talamas is expanding his studies on perceptions of intelligence in various ways. At the moment, he is collaborating with researchers in Singapore testing an intervention to get students to sleep better by showing them how it effects their perceived intelligence.

Talamas plans on taking his research further by looking at how factors such as stress and fitness effect perceptions of attractiveness, health and intelligence. He just completed a study in collaboration with the University Sports Centre investigating how changes in fitness can influence a more healthy skin colour. He is also interested in pursuing how personality and individual differences, such as grit and conscientiousness, influence both academic and sports performance.

Credits

Graphics and design by the University of St Andrews digital communications team. Content written by Maria Drummond and Jenny Hamrick, digital communications team, with contributions from Sean Talamas. Video, audio and additional photography by the student-run Lightbox Creative St Andrews. Mindscape podcast by Miranda Strachan.

Thanks

Sean Talamas for his contributions, access to research, and attractive-comparison video creation.

Willypete for his patience and good manners during filming; he deserves more snacks.

Alyssa Chafee and Lightbox Creative for the videos and photographs.

Miranda Strachan for providing the Mindscape podcast interview with Sean Talamas.

Sources

- Strachan, Miranda. "Episode 1." Mindscape (2016). Podcast. 5 April 2016.

- Talamas, Sean. "Perceptions of Intelligence and the Attractiveness Halo." Thesis. University of St Andrews, 2015. Print.

- Talamas, Sean, Kenneth Mavor, John Axelsson, Tina Sundelin, and David Perrett. "Eyelid-openness and Mouth Curvature Influence Perceived Intelligence beyond Attractiveness." Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 145.5 (2016): 603-20. PsycARTICLES. Web. 24 May 2016. DOI:10.1037/xge0000152

- Talamas, Sean, Kenneth Mavor, and David Perrett. "The Influence of Intelligence on the Endorsement of the Intelligence–attractiveness Halo." Personality and Individual Differences 95 (2016): 162-67. Web. 24 May 2016. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.053

- Talamas, Sean, Kenneth Mavor, and David Perrett. "Blinded by Beauty: Attractiveness Bias and Accurate Perceptions of Academic Performance." PLoS ONE 11.2 (2016). Web. 24 May 2016. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0148284

Contact

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +44 (0)1334 46 2108