The art of friendship

Emerson considered friendship in terms of “truth and tenderness”, Aristotle described friendship as the generous act of holding a mirror up to each other, Montaigne as a “holy name”, and Thoreau as “a grand stake for which the game of life may be played”.

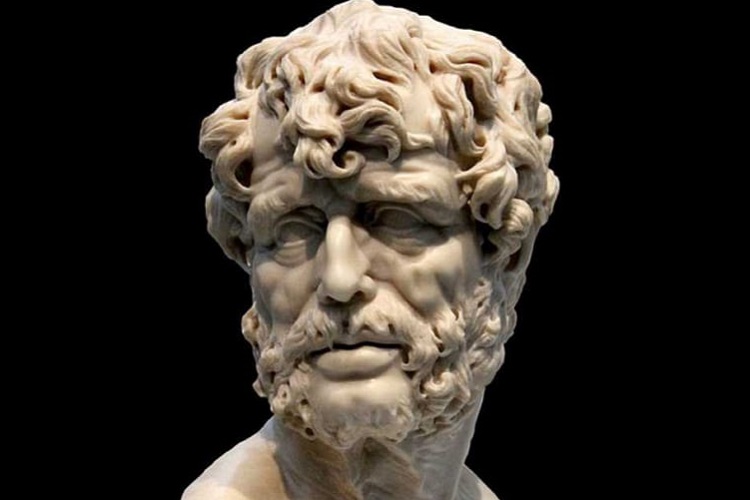

Today it may be difficult to inoculate the integrity of the word “friend” against commodification, social media misuse, and overuse. However, Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic provide some helpful guidance on how to tell the difference between uses and misuses of the term:

“If you consider any man a friend whom you do not trust as you trust yourself, you are mightily mistaken and you do not sufficiently understand what true friendship means… When friendship is settled, you must trust; before

“…no one can live happily who has regard for himself alone…”

The importance of being able to identify and value true friendships cannot be underestimated, as Seneca suggests friendship rewards not only individuals but also holds humanity together:

“Friendship produces between us a partnership in all our interests. There is no such thing as good or bad fortune for the individual; we live in common. And no one can live happily who has regard for himself alone and transforms everything into a question of his own utility; you must live for your neighbor, if you would live for yourself.”

Friendship requires cultivation

To succeed in lasting friendships, however, requires application, and tenacity of affection. As Mary Wollstonecraft argued in a letter written in Norway (1796), four years after she laid out the principles of emancipation in her landmark treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Women, friendship’s common pitfall is that it suffers when flattery and proximity fade.

“It requires more cultivation of mind to keep awake affection, even in our own hearts, than the common run of people suppose. Besides, few like to be seen as they really are; and a degree of simplicity, and of undisguised confidence, which, to uninterested observers, would almost border on weakness, is the charm, nay the essence of love or friendship, all the bewitching graces of childhood appearing again.”

There are many examples of friendships successfully sustained, that have enriched St Andrews and its connections. Principal Irvine’s friendship with Edward Harkness led to the creation of St Salvator’s Hall. The merchant and adventurer Alexander Berry’s life-long friendship with fellow alumnus George Walker is recorded in letters preserved in the University collections. Trailblazer Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman to matriculate at the University of St Andrews, was inspired by a life-long friendship with the feminist Emily Davies, who encouraged Elizabeth to become a career woman. More recently, letters recording the 18th-century friendship of alumni Thomas Spankie and John Warden brought Ro Spankie, Principal Lecturer in Architecture and the Built Environment at the University of Westminster, to St Andrews to find out more.

How to remain friends

The poet and philosopher David Whyte explores the challenge of keeping friendships alive in Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words (2015):

“In the course of the years a close friendship will always reveal the shadow in the other as much as ourselves. To remain friends, we must know the other and their difficulties and even their sins and encourage the best in them, the leading creative edge of the incarnation, thus subtly discouraging what makes them smaller, less generous, less of themselves.”

He warns of the dangers of underestimating the importance of friendship:

“A diminishing circle of friends is the first terrible diagnostic of a life in deep trouble: of overwork, of too much emphasis on a professional identity, of forgetting who will be there when our armored personalities run into the inevitable natural disasters and vulnerabilities found in even the most average existence.”

A growing circle

The pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell, in a thoughtful diary entry on the first day of 1855, reinforced the idea that our goal should be a circle of friends:

“A friend is not to be found in the world such as one can conceive of, such as one needs, for no human being unites so many of the attributes of God as we feel our nature requires. We have therefore a circle whom we call friends, giving a name to the whole, which perhaps in its singular occupation might be used for the combination. Out of the whole circle we may make up a single friend. We love them all, but we love the union of all better.”

Here Maria Mitchell seems to echo the sentiment of the early-20th-century poet Rainer Maria Rilke who said: “I live my life in widening circles.”

#Graditude

David Whyte develops the sense of appreciation, making clear the love of friends is separate from utility:

“The ultimate touchstone of friendship is not improvement, neither of the other nor of the self. The ultimate touchstone is witness, the privilege of having been seen by someone and the equal privilege of being granted the sight of the essence of another; to have walked with them and to have believed in them, and sometimes just to have accompanied them for however brief a span, on a journey impossible to accomplish alone.”

For philosopher Alexander Nehamas this means there is no one, settled self that we discover over time. Rather, we continually shape each other and ourselves through our friendships.

Keep reading: Alumni of the University of St Andrews can keep their library membership post-graduation for a reduced charge of £20 each year. This allows you to borrow up to 10 items (but no access to DVDs, short loan, audiovisual material or online resources).

Keep in touch with your friends: Saint Connect provides a secure, social platform for group chats, alumni clubs and connecting with mentors.