Bacteria use chemical harpoons to hold on tight to their hosts

The global threat of widespread bacterial resistance to antibiotics is one of the greatest challenges facing science and medicine.

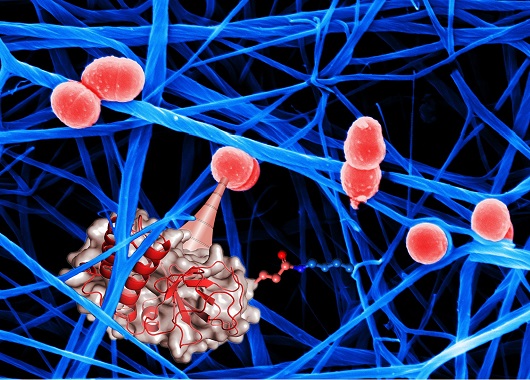

The breakthrough discovery of bacterial “chemical harpoons” could pave the way for a new approach to treating bacterial infections by “disarming” bacteria instead of trying to kill them with antibiotics. These chemical harpoons can be compared to a superglue, whereas all previously known bacterial binding mechanisms can be likened to weak adhesives that require large contact areas for strong binding.

New research led by the University of St Andrews and the John Innes Centre and published today in the scientific journal eLife reveals how Streptococcus pyogenes, the cause of many infections ranging from the common strep throat to the life-threatening “flesh-eating disease”, use chemical harpoons to attach themselves to the body.

Importantly, this tactic is shared by many other bacteria that infect humans, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most common cause of pneumonia in adults, and Clostridium difficile, notorious for causing severe gut infections in hospitalised patients.

The study was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and led by Dr Uli Schwarz-Linek, structural biologist of the Biomedical Sciences Research Complex at St Andrews, and Dr Mark Banfield, John Innes Centre in Norwich, in collaboration with Professor Manfred Rohde (Helmholtz Center for Infection Research, Braunschweig, Germany).

“Among the weaponry of bacteria are protein molecules within hair-like structures displayed on their surfaces,” said Dr Uli Schwarz-Linek.

“These serve the important purpose of allowing bacteria to cling to host tissues, such as the cells lining the lung or the gut. We have discovered how bacteria use surface proteins to achieve this important step in infections using a surprising and particularly efficient method.

“I believe these findings may significantly change our view of how bacteria colonise their hosts. Our discoveries open an avenue for the development of molecules that can deactivate the chemical harpoons and therefore prevent bacteria from gaining a foothold in the body. This is of great interest since it concerns a topic of the highest possible relevance for our society – the fight against bacterial infections.”

Dr Mark Banfield from the John Innes Centre, who co-led the study, said: “It has been very exciting to build on our initial discovery of the unusual bond these bacteria make with their host and to now appreciate how that bond works – all enabled through international collaborative research. Further, using the powerful X-rays available at Diamond Light Source, the UK’s synchrotron facility, we were able to visualise this bacteria/host interaction at the atomic level.”

Dr Des Walsh, Head of Infections and Immunity at the Medical Research Council, said: “Before we can develop new ways of fighting antimicrobial resistance (AMR), we need to fully understand how bacteria survive. It is exciting that MRC-funded researchers have discovered a unique insight into how bacteria invade and seize healthy tissue. We recently awarded an additional £5m towards AMR research, and we will continue to support the best, collaborative research that explores new and promising ways to solve the challenge.”

Notes to news editors

An internal thioester in a pathogen surface protein mediates covalent host binding’ is published by eLife http://elifesciences.org/content/4/e06638

Photographs are available. Dr Schwarz-Linek is available for interview. Contact Communications Office.

Issued by the University of St Andrews Communications Office, contactable on 01334 467310 or [email protected].

Category Research