Trumping medieval cruelty?

New research from the University of St Andrews sheds light on the historical use of waterboarding as a severe form of torture and its re-emergence at the highest levels of Trump’s administration.

New research from the University of St Andrews sheds light on the historical use of waterboarding as a severe form of torture and its re-emergence at the highest levels of Trump’s administration.

The study, Historicizing waterboarding as a severe torture norm, published in the journal International Relations (20 September 2018), focusses on the historical evidence of waterboarding from pre-modern Europe, where it was understood as a severe form of torture, and the modern re-emergence and endorsement of this technique by US security agencies.

Post-9/11, waterboarding was adopted by the CIA as a form of torture to extract intel, much of which has since been documented through Senate Committee hearings and in the media, to widespread condemnation. Soon after taking office, President Obama signed a new Executive Order in 2009 barring the CIA from using harsh interrogation methods beyond those permitted by the US military.

The study shows that in 2018, in Trump’s America, there is a growing trend towards a permissive stance on waterboarding and its re-emergence at the highest levels of American government. Gina Haspel, accused of overseeing waterboarding at CIA black-sites, was this year confirmed as Director of the CIA. Meanwhile, Donald Trump has promised that he would, “…bring back a hell of a lot worse than waterboarding…” because we’re “…living in medieval times…” and we’re fighting “violent people, vicious people”.

Trump’s invocation of the Middle Ages taps into widespread perceptions of medieval society as singularly barbaric. Yet, in attempting to persuade the American public that waterboarding is unpleasant but essentially harmless, the Bush administration, and potentially the Trump administration, indulged in a practice that medieval interrogators considered one of the cruellest techniques of the torture chamber. If ‘vicious’ medieval society was more attuned to the torturous reality of waterboarding than a 21st-century liberal democracy, we surely have a problem.

Dr Rory Cox, Lecturer in Late Mediæval History at the University of St Andrews, notes that debates regarding the utility and morality of torture date back to the ancient world. Aristotle observed that “evidence from torture may be considered utterly untrustworthy”, while Roman jurists warned that the information obtained “is weak and dangerous”. In the Middle Ages, those who existed on the periphery of ‘civilized’ society – slaves, Jews, heretics – lacked legal protections and were more likely to be tortured. Parallels could therefore be drawn between this and the modern treatment of minorities or those detained as part of the War on Terror.

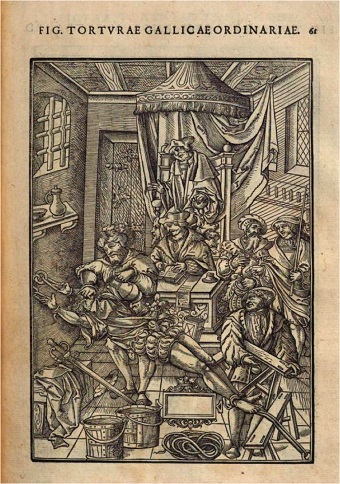

Historically, Dr Cox shows that waterboarding and other tortures were used to extract confessions, but also to punish, intimidate, or exact vengeance. Public spectacles of torture allowed authorities to communicate power and enabled the public to participate vicariously in the punishment of individuals who had injured the community. Perhaps support for waterboarding in 21st-century America also satiates these desires, as a continuing revenge for 9/11 and other attacks.

From the 15th century, the Spanish Inquisition regularly used la toca (‘the cloth’), but only after victims were flogged up to 200 times. Waterboarding was regularly employed in the French judicial system from the 14th century up until the late 18th century, where it was used if the strappado – hoisting by wrists bound behind the back – was unsuccessful. In 1651 the diarist John Evelyn described a French prisoner as being “to all appearances dead with pain” after a waterboarding session.

The lack of external physical scarring produced by waterboarding has been crucial to its modern characterisation as ‘torture-lite’. However, medical and psychological research shows that physical pain is not the most important determinant of traumatic stress in victims of torture. Feelings of humiliation, helplessness and genuine fear for one’s life are more powerful in creating long-term trauma. Waterboarding’s efficacy is a distinctive capacity to induce rapidly the panic and pain of impending death: the “poor wretch is in the same agony as persons ready to die”, as a 17th-century Dutch chronicler described it. Much later, a French-Algerian journalist, Henri Alleg, recalled the “insupportable agony” of being waterboarded by French soldiers in 1957.

Dr Cox said: “Since the Middle Ages, waterboarding has been judged to be worse than flogging, racking and the strappado: techniques that any sane person in a modern liberal democracy would baulk at defending or excusing. This history seriously undermines re-imaginings of waterboarding as ‘torture-lite’. If even medieval society – so commonly condemned as barbaric – recognised the brutality of waterboarding, then we should be ashamed that in the 21st century some are willing to condone it. Those who have authorised or employed waterboarding, or would seek to do so, violate US domestic law and international law. Such individuals should be criminally prosecuted; they should not lead the US’s foremost intelligence agency or sit in the Oval Office.”

The paper Historicizing waterboarding as a severe torture norm is published in the journal International Relations and is available online.

Please ensure that the paper’s DOI (doi.org/10.1177/0047117818774396) is included in all online stories and social media posts and that International Relations is credited as the source.

Image caption: Torturae Gallicae Ordinariae (Standard Gallic Torture), Milles de Sauvigny Praxis Criminis Persequendi (Paris, 1541)

Dr Rory Cox is a Lecturer in Late Mediæval History and Associate Director, St Andrews Institute of Intellectual History.

Dr Cox is also Co-Editor, Global Intellectual History.

Issued by the University of St Andrews Communications Office.