Families at war

Warfare between human groups ignites conflicts between the selfish interests of different family members and even between a warrior’s own genes, say researchers at the University of St Andrews.

The new study – published tomorrow (22 February 2017) by Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B – also suggests that conflict between maternal and paternal genes could explain violent behaviours in contemporary humans.

The research, led by Alberto Micheletti, used evolutionary models to investigate disagreements between a would-be warrior’s mother and father over whether or not he should go off to war.

Mr Micheletti and his colleagues Graeme Ruxton and Andy Gardner performed a mathematical analysis to investigate the interplay and conflict between family members over time – and found that fathers were more warmongering while mothers were more pacifying.

Mr Micheletti, a PhD researcher at the University’s School of Biology, explained: “This makes sense from a selfish-gene perspective. Going off to fight in a war is an example of a behaviour where the individual doing it might actually pay a high cost themselves, but which also offers benefits to the others in their social group.

“In prehistoric societies, women generally lived with their husbands’ families, and as a consequence fathers were more genetically related to the rest of the group than were mothers. So individually-costly but group-benefitting behaviours like participation in warfare were more likely to be favoured by fathers than by mothers.”

Recent years have seen an explosion of multidisciplinary interest in ancient human warfare, however conflicts of interest of family members remain a relatively underexplored factor in evolutionary studies. Until now little consideration has been given to which parties influence the decision to go to war and how their motivation may differ.

Surprisingly, the researchers found that these disagreements can even extend to the genes parents pass onto their children.

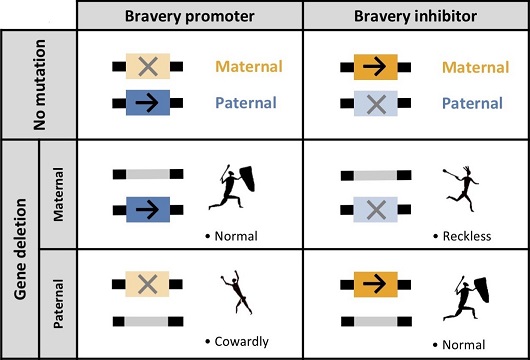

Mr Micheletti continued: “The warrior’s own genes disagree about whether he should participate in warfare, with paternal-origin genes being more warlike and maternal-origin genes favouring less aggression.

“An interesting consequence of this is that genes may end up having different effects depending on which parent they came from; this is called genomic imprinting.”

The research showed that such imprinting can make humans vulnerable to the effects of mutation and other genome errors, resulting in extreme psychological disorders that could go some way towards explaining societally-damaging intergroup violence and other behavioural problems.

“Ultimately, violent conflict between human groups cannot be fully understood without taking into account conflicts at two other levels – individuals and their genes.”

“Taking a multilevel perspective allowed us to shed light on a long-standing question in anthropology and to propose a novel explanation for violent behaviours,” he concluded.

Photo captions

Top: Dad’s genes are from Mars, Mum’s genes are from Venus (credit: detail from Mantegna’s Parnassus, courtesy of Wikimedia – public domain)

Bottom: Conflict between a warrior’s maternal and paternal genes, detail from Figure 4 of the study (credit: human figures from the George Stow collection at Iziko South African Museum, derived from The Digital Bleek and Lloyd, with permission)

Background

‘Intrafamily and intragenomic conflicts in human warfare’ by Alberto Micheletti, Graeme Ruxton and Andy Gardner is available online.

The research was supported by the School of Biology at the University of St Andrews and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

Issued by the University of St Andrews Communications Office, contactable on 01334 462530 or via [email protected].

Category Research