Research review of the year

This year has been buzzing with brilliant research right across the University of St Andrews. As 2025 draws to a close, Research Spotlight has been looking back at some of the brightest sparks from the last 12 months. While it would be impossible to capture the entire scope of fizzing research in this short round-up, here’s a month-by-month snapshot of our research.

The bat signal was received loud and clear in January as Professor Sonja Vernes discovered that bats were able to tolerate coronaviruses without becoming ill. The paper, published in Nature, showed that bats have more genetic adaptations in immune genes than other mammals. Researchers found that in some bats, they can reduce the production of SARS-CoV-2 by up to 90 percent. These results could help to develop new medical approaches to combat viral diseases.

February started with a bang – literally. Dr Helen Innes from the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences was able to precisely date a volcanic super-eruption by identifying microscopic ash particles in polar ice cores. This month also had one of the biggest news splashes this year, when Dr Ellen Garland from the Scottish Oceans Institute co-wrote a paper which found that whale song had a human language like structure.

Staying with the aquatic, March saw Dr Chris McKnight answering a simple but fundamental question – why seals don’t drown.

In April, the mechanism which controls the wiggle of the Red Flour Beetle was discovered by Dr Maarten Zwart, Dr Stefan Pulver and team in the School of Psychology and Neuroscience. This little insect ruins around 20% of the worlds grain and flour stores each year and is a major threat to global food security, so it’s hoped that this discovery will lead to smart ways of combating the pest.

This year also saw some data resulting from the fallout of the Covid years, revealing how it has changed our society. Dr David McCollum’s work in May, from the School of Geography and Sustainable Development, showed that rather than helping struggling UK regions attract high-skilled workers, working from home could be exacerbating the spatial and social inequality which persisted before the pandemic.

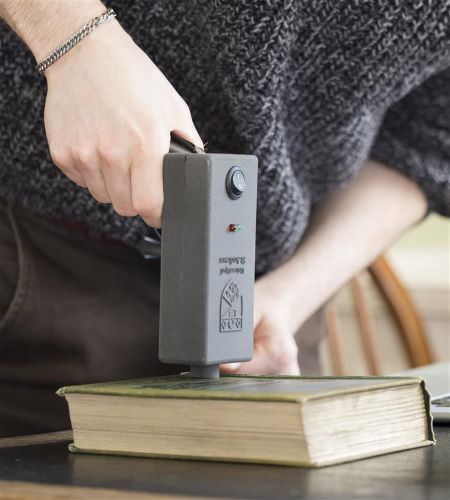

June saw a collaboration between Libraries and Museums and the School of Chemistry, who came up with an ingenious hand-held device which could identify green ‘toxic’ books. The pigments used for binding green books created low levels of arsenic, which cause health problems through prolonged exposure. Libraries and collections around the world have been isolating huge numbers of books to try and mitigate the risk, but the tool was able to easily identify what is safe and what is not.

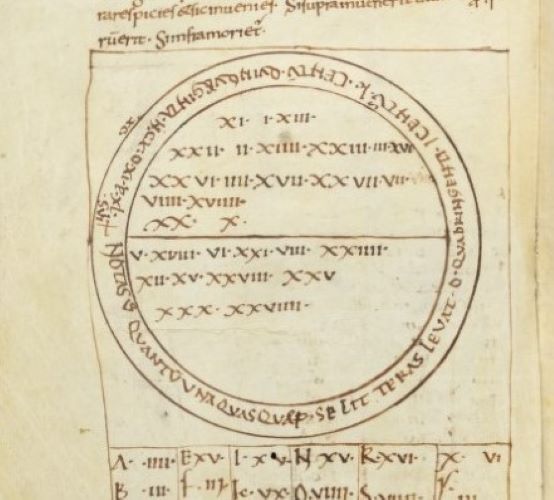

Also in the world of books came research from the School of History’s Professor James Palmer, whose work compiling medicinal wisdom from the Middle Ages contained surprising information about lizard shampoo and spheres of death.

In July, just in time for a summer tipple, chimpanzee expert Dr Cat Hobaiter published a paper, showing that feeding on fermented fruits is an important behaviour in the lives of African apes, and one that explains why they, and we, evolved the ability to digest alcohol efficiently.

In August Dr Sabine Hyland from the School of Divinity published work upending perceived wisdom about the Inka empire and their social structures, by analysing hair contained in ancient inca string writing called Khipus. From ancient forms of communication to the future of them, Professor Andrea Di Falco and his team in Physics and Astonomy found a way of using Organic Light Emitting Diodes and Holographic Metasurfaces as overcoming the main barriers to hologram technology being used more widely.

In September, we explored space, both in the great beyond and in our own heads. Dr Alexander Russell led on a paper from the School of Mathematics and Statistics which found solar flares to be six times hotter than previously thought, while Dr Ryan MacDonald from Physics and Astronomy was part of a team who made a tentative analysis of what might be the first observable atmosphere of an exoplanet in the ‘habitable zone’. While this work went interstellar, Professor Jamie Ainge from the school of Psychology and Neuroscience revealed the mechanism behind the brain’s built in distance tracker.

In October Dr Aleks Scholz and his team discovered a mysterious rogue planet, a rare type of planet that drifts freely through space, untethered to any star, which was eating space. The rogue planet, about 620 million light years away, is currently eating up gas and dust from its surroundings at a rate of six billion tonnes a second.

In November, Dr Patrick Pomeroy’s field-based research contributed to a paper showing that seal milk was more complex than human breast milk, marking a massive step forward in our understanding of mammals. Fieldwork was key, too, when Dr Tim Kinnaird and Professor Richard Bates from the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences helped confirm the details of a massive, neolithic pit structure recently discovered during geophysical survey around the Durrington Walls Henge, Wiltshire.

Closing the year, December saw an amazing new discovery from the School of Chemistry, Dr Amit Kumar was able to use household plastic waste and turn it in to the base for anti-cancer medications, while Dr Jo Hale from the School of Geography and Sustainable Development discovered that being sociable at Christmas might just protect the brain in later life.

Phew. This is just a little Christmas taster menu of the incredible research both published and ongoing which took place across 2025. Time for a quick break, a bit of Christmas pudding, then back to work! See you in 2026.

Category University news