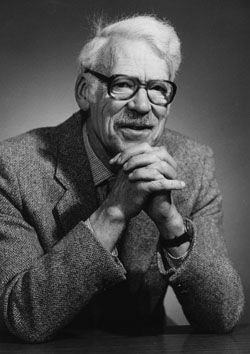

Sir Kenneth Dover: an appreciation

Professor Stephen Halliwell, Head of the School of Classics, wrote the following in tribute to renowned classicist and former Chancellor, Sir Kenneth Dover, who died at the weekend (Sunday 7 March 2010), aged 89. An edited version of this obituary appears in today’s Guardian newspaper.

Sir Kenneth Dover, one of the world’s greatest Hellenists, has died at the age of 89. His career of pre-eminent academic distinction included the presidency of Corpus Christi College, Oxford (1976-86), the presidency of the British Academy (1978-81), and the Chancellorship of St Andrews University (1981-2005). Dover was a towering, renowned figure in the study of ancient Greek language, literature and thought; very few indeed could approach the range and quality of his scholarship, especially the synthesis of philological, historical and cultural acumen which marked all his work. His name became known to a wider public partly for his groundbreaking book Greek Homosexuality in 1978, and partly as a result of the controversy which erupted after publication of his candid autobiography, Marginal Comment, in 1994.

Sir Kenneth Dover, one of the world’s greatest Hellenists, has died at the age of 89. His career of pre-eminent academic distinction included the presidency of Corpus Christi College, Oxford (1976-86), the presidency of the British Academy (1978-81), and the Chancellorship of St Andrews University (1981-2005). Dover was a towering, renowned figure in the study of ancient Greek language, literature and thought; very few indeed could approach the range and quality of his scholarship, especially the synthesis of philological, historical and cultural acumen which marked all his work. His name became known to a wider public partly for his groundbreaking book Greek Homosexuality in 1978, and partly as a result of the controversy which erupted after publication of his candid autobiography, Marginal Comment, in 1994.

Dover was born in London and educated at St Paul’s School and Balliol. He showed an early fascination for the varieties and intricacies of language, going so far as to teach himself the grammar of some Pacific languages as an adolescent. A capacity for close, subtle investigation of what linguistic usage can reveal about the fabric of human experience was to remain his hallmark, but he distanced himself from theoretical linguistics (‘my attempts to read Chomsky are enfeebled by the rapid onset of boredom’, as he put it). His undergraduate studies were suspended for war service in the Western Desert and Italy, earning him a mention in dispatches but also bringing him into contact with working-class soldiers whose unpretentious attitudes made a lasting impact, he maintained, on his conception of life even in Greek antiquity. He returned to Oxford in 1945 to continue an academic trajectory illuminated by a succession of prizes and scholarships. In 1948 he began doctoral study under the great historian Arnaldo Momigliano (who later said there was nothing he could teach Dover), but this was overtaken by appointment to a fellowship of Balliol in the same year.

The early 1950s saw him build up a prodigious mastery of Greek language and literature, above all in three areas (comic drama, historiography, and oratory) in which he was to become a world authority. When he left Balliol in 1955 for the chair of Greek in St Andrews, it was with the general expectation that he would succeed Eric Dodds (author of The Greeks and the Irrational) to the Regius chair in Oxford; but when that opportunity was presented in 1960, family considerations led him to decline it. He remained in St Andrews till 1976. During his two decades there he became the finest Hellenist of his generation in Britain and author of a succession of acclaimed books, including major commentaries on Aristophanes’ Clouds and on parts of Thucydides’ History.

Always a polished stylist, and, in his prime, a superbly assured lecturer, Dover was capable of adapting his expertise for very different audiences, even if a 1980 television series on the Greeks was blighted by maladroit directing. The Greeks (1980), for instance, a book commissioned in connection with the TV programmes, distils many of his guiding ideas for students and general readers, while Greek Word Order (1960) is an exhibition of formidably meticulous analysis on a subject so improbably specialised to some eyes that I have seen its title ‘corrected’ to Greek World Order. Highly characteristic of Dover’s methods and mentality was Greek Popular Morality (1974), a richly documented attempt to reconstruct the value-system of fourth-century BC Athens from the various argumentative strategies used by orators in the city’s courts and political assembly. This work brought out his concern to try to understand the Greeks always in realistic rather than idealised terms. His complementary suspicion of abstractions engendered an impatience with philosophical aspirations (not least Plato’s) which formed one of his few intellectual weaknesses.

The production of substantial books, together with visiting positions in the USA and elsewhere, continued after Dover’s move to the presidency of Corpus in 1976 (and his knighthood in 1977). Particular attention inevitably focussed on Greek Homosexuality (1978; subsequently translated into several languages, Japanese among them), which treated the topic with unprecedented openness, nuanced definition, and a full panoply of scholarly techniques. The work drew together the evidence of literature (not least, a prosecution speech in a sensational Athenian court case), visual art (Dover inspected hundreds of sexually explicit vase-paintings, often in the basements of museums), history, mythology, and even philosophy, to present a compelling picture of the complex web of sexual and social practices, as well as the ambivalent mores, that constituted the phenomena now grouped together under the label of Greek homosexuality. The book proved a turning-point in the modern study of ancient sexual cultures, greatly stimulating the growth of this field in the 1980s (and not just among specialists: Michel Foucault was among those influenced by it). Later in life Kenneth was sometimes impatient that the subject had become an academic industry and that Greek Homosexuality had become the best known of his works, partly occluding what he felt to be his own central achievement as a historian of the Greek language. But the book is deservedly admired for harnessing scholarly sophistication to a shrewd and broad-minded historical imagination. If parts of its argument have been challenged, it remains an indispensable resource and makes some recent contributions to the subject look tawdry.

The later years of Dover’s career continued to be marked by important publications, including two volumes of collected papers, a commentary on Aristophanes’ Frogs, and his last book, The Evolution of Greek Prose Style (1997), a difficult but searching essay in historical stylistics. Dover’s eminence led him, however, into the thick of controversy. His presidency of the British Academy was marked by acrimonious contention over Anthony Blunt’s fellowship after the latter’s exposure as a Soviet spy: while privately favouring Blunt’s expulsion, Dover felt obliged, in the interests of the Academy’s unity, to maintain public even-handedness, a policy which made him the target of animosity from opposing camps. But he was more trenchant in declaring his own convictions when in 1985 he was the only serving Oxford head of house to lend open support to opposition to a proposed honorary degree for Margaret Thatcher.

The same year brought to a head a protracted problem in Corpus over the chronically unstable conduct of Trevor Aston, a history fellow whose bitter disputes with the college led Dover, as he subsequently revealed, to wish him dead and even to contemplate pushing him into suicide. When Aston did kill himself (for independent reasons), Dover felt immense relief, which he described with ruthless honesty in Marginal Comment. This frankness, which soured his relations with certain Corpus Fellows, shocked some people, as did the book’s occasional passages of personal sexual detail. But even if his judgement of tone in respect of the latter was naive, Dover had taken a principled decision to write autobiography in a confessional mode, one of the oldest traditions of the genre, and he thought that some reactions to his book ostensibly preferred hypocrisy to truthful handling of one’s feelings and experiences. It is unfortunate that the furore over these aspects of Marginal Comment obscured the work’s elegantly written attempt to explore the motivations and the understated passions, that had shaped a life of academic enquiry at the highest level.

The distinctive value of Kenneth Dover’s remarkable body of work lies not just in its consummate linguistic and historical adeptness, but in its fusion of these qualities with an imaginative insight that never ceased to find the whole gamut of human behaviour worthy of attention and explanation. To a degree extremely rare among top-rank academics, Kenneth was genuinely interested in all dimensions of life – from the sounds of people’s voices, as he sometimes said, to the largest ideas which inform their actions in the world. Students and colleagues found him exemplary not for his pursuit of a method or ideology (he was scrupulously undidactic) but for the finesse with which he displayed how the best historical thinking can fuse technical excellence with deeply reflective understanding. His death feels like the end of an era in classical scholarship. His extensive published legacy will always be a landmark in the study of the ancient Greeks.

His wife Audrey, whom he married in 1947, died two months before him. They are survived by a son, Alan, and a daughter, Catherine.

Stephen Halliwell

Kenneth James Dover, academic, born 11 March 1920; died 7 March 2010

Category University news