Cancer drug may cause women to grow new eggs

Women treated with a common chemotherapy drug combination have more young eggs in their ovaries afterwards, research has found.

A small study indicates that a therapy commonly used to target Hodgkin’s lymphoma appears to improve the condition of egg-producing tissue in women’s ovaries.

Researchers say it is too soon to link the outcome to fertility, but believe more research is needed to better understand the findings and their implications.

Scientists from the University of Edinburgh worked with colleagues from the School of Computer Science at the University of St Andrews to analyse samples of ovary tissue donated by 14 women who had undergone chemotherapy, and from 12 healthy women.

They found that the ovaries from eight of the cancer patients, who had been treated with a drug combination known as ABVD, had a much greater incidence of immature, or non-growing, eggs compared with tissue from women who had received a different chemotherapy, or from healthy women of a similar age.

The ovary tissue was seen to be in healthy condition, appearing similar to tissue from young women’s ovaries.

If further research can reveal the mechanism by which treatment with ABVD results in increased production of eggs, this would aid understanding of how women might be able to produce more eggs during their lifetime, which was until recently thought to be impossible.

Researchers had set out to better understand why treatment with ABVD is one of the few cancer drug combinations that does not impact on women’s fertility.

Future studies will examine the separate impact of each of the four drugs that combine to make ABVD – known as adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine – to better understand the biological mechanisms involved.

The study, published in Human Reproduction, was supported by the Medical Research Council.

Lead researcher Professor Evelyn Telfer of the University of Edinburgh’s School of Biological Sciences said: “This study involves only a few patients, but its findings were consistent and its outcome may be significant and far-reaching. We urgently need to know more about how this drug combination acts on the ovaries, and the implications of this.”

Tom Kelsey, of the University of St Andrews’ School of Computer Science, who led the modelling and analysis said: “More research is needed but the suggestion is that the textbook understanding of the biological clock is wrong: instead of an ever-declining reserve of eggs, it’s possible to dramatically increase the population.”

Notes to Editors

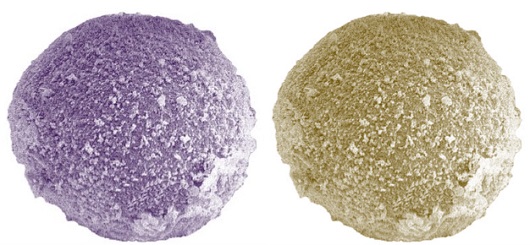

Image shows a close up of a human egg cell

Issued by the University of St Andrews Communications Office, contactable on 01334 462530 or via [email protected].

Category Research